Microplastics: Ani’s maritime adventure, bottles to fabric, and end of life (or afterlife) for plastics.

Early last month I had the absolute pleasure of heading north to Seattle and spending 4 days on an incredible floating classroom called the Schooner Adventuress. I was invited back after 6 years of absence to participate in a particularly dear-to-my-heart program called Girls at the Helm. Onboard were:

- 18 girl participants between 7th and 12th grades

- 13 adult self-identified lady crew members

- 5 self-identified lady mentors who have careers in STEM fields: science, technology, engineering, and mathematics

This yearly trip is an opportunity to demonstrate to girls that women are capable, strong, and intelligent leaders in areas typically dominated by men. Studies show girls are more likely to pursue any particular career if they see a woman in that position. With a female captain, female engineer, female mate, and an all-female crew on board, we hope to inspire those girls to reach for their dreams.

One of the mentors was Dr. Julie Masura who studies the presence and abundance of microplastics in marine surface water, bed sediments, and beach sands. She is a Senior Lecturer and Research Scientist at the University of Washington Tacoma. Julie brought a special surface towing net to collect marine debris with the girls and look at what is in the waters of Puget Sound. My experience onboard as well as my time with Julie is what prompted this post.

This is a HUGE and overwhelming topic.

My full-time job is to educate people about waste reduction, upstream and downstream impacts of consumption, and how to recycle correctly. I spend a lot of time reading and digesting related topics. Plastic has been the toughest for two main reasons. First, because of its current status (or lack of status) in the recycling market. And second, due to the attention it has received because of its impacts (especially from single-use) on climate change and sea life. There are a lot of opinions to dig through and there’s an excruciatingly large amount of information to understand. So I’m going to share with you what I have learned, even if it is just the tip of the iceberg.

Ani Kasch peering at microplastics pulled out of Puget Sound.

What is plastic and how is it made?

Most plastics in use today are made from petroleum; either from crude oil or natural gas. Here is a quick step by step of how it’s made taken directly from this National Geographic video.

- Extraction: Fossil fuels — either natural gas or crude oil — are extracted from the ground.

- Refinement: Fossil fuels are made into products: ethane from crude oil and propane from natural gas.

- Cracking: Products are broken down into smaller molecules — ethane into ethylene, propane into propylene.

- Polymerization: A catalyst is added to the cracked product that links molecules together to form polymers (long flexible chains of chemical compounds) called resins. This state allows the plastic to be easily molded and stretched into useful shapes. Ethylene becomes polyethylene, propylene becomes polypropylene.

- Final Product: At that point, the resins are melted and broken up into pellets that are then sold to manufacturers.

5 quick facts about plastic

- Plastic can usually be recycled only once or twice because the polymers degrade, get shorter, and therefore become weaker during the recycling process.

- Not all plastic can be recycled! In your Deschutes County curbside bin, it is bottles tubs and jugs. Not sure? Throw it in the trash or ask ani@envirocenter.org!

- The chasing arrows symbol you see on plastic does not mean that plastic is recyclable. The number inside the arrows tells you what types of chemicals are used to make the plastic — it is the resin identification code.

- Paper coffee cups are lined with polyethylene (plastic), which is why they aren’t recyclable in our curbside bin.

- People in the US throw away 50 billion single-use coffee cups per year. #BringYourOwnCup

Ok, so what are microplastics, and why does Julie study them?

According to Julie, “microplastics are any polymer with a long diameter < 5mm” — so basically, tiny bits of plastic. She characterizes other sizes in her studies, but that is the broad definition. Microplastics have become ubiquitous in our environment. Julie believes it is very important to understand how common microplastics are, where they end up, and how they impact our environment and ourselves.

Where do microplastics come from?

As any plastic gets used, reused, and recycled, its polymers start to break down into those little microplastic bits that end up in our environment–locally, regionally, and globally. Some microplastics are big enough to be seen with the naked eye, but others are microscopic. Here are a couple of examples:

- Plastic bags can easily blow away and end up in a bush whose branches tear it to pieces that end up in the river.

- Washing and wearing synthetic clothing releases microfibers, a type of microplastic, into the water. Think of our yoga pants, fleece mid-layers, and latex bike shorts for example. Check out this incredible (albeit slightly disheartening) video from The Story of Stuff Project showing how it happens.

- The process of turning old plastic bottles into those synthetic fabrics has a byproduct of microplastic bits. Check out this amazing video from the insides of several factories showing how a solid piece of plastic is made into a soft fluffy fleece jacket!

- Microplastics are often in your cleaning products in the form of microbeads.

What did you find in the net on Adventuress?

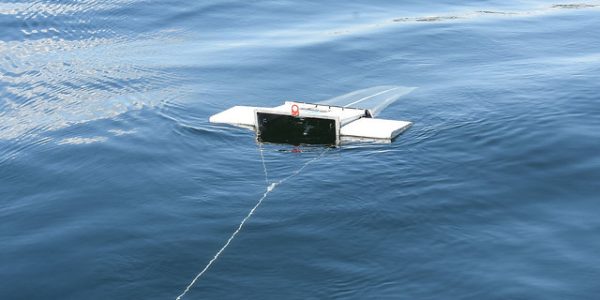

The net that Julie brought on board is designed to float on the surface of the water using hollow wings. Thus the contraption has earned the name “Manta Net” after the large marine ray. As the boat Adventuress sails through the water, the net is towed behind collecting any marine debris in its path. All of the following photos were taken by (and are used with permission of) Girls at the Helm founder Elizabeth T. Becker. Check out her amazing work at www.seaportphotography.com.

- Prepping the Manta Net for deployment

- Deploying the Manta Net

- Towing the Manta Net and collecting marine debris

After the net is hauled in, a hose is used to rinse all the debris down to a bottle at the tip of the net called the “cod end”. Next, all the contents of the net are poured into a pan for examination.

- Dr. Julie Masura explaining about how the net functions

- Julie looking through the catch with participants

- Deckhand Sophia helping Julie’s graduate students with the net

The participants got to look through everything we pulled up. There was a fair amount of seaweed, plankton, and fish along with a surprising amount of plastic. Although sometimes hard to see, it is there when you look closely. It made me think: how much plastic do I inadvertently swallow? And how is it affecting me?

- Am I ingesting plastic while swimming in salt or freshwater?

- How about while showering at home?

- While eating fish that ate the plastic?

- Or is the stuff in bathroom products I use regularly — even when the label says it’s safe?

Yikes. There is concern about the negative effects of plastics on human health due to the chemicals and toxicity in them. Here is an article from the Oregon Environmental Council where you can learn more.

Um, Ani? We live in the desert. We don’t have an ocean anywhere around.

Here’s a quick geography lesson. Do you know the Deschutes River, the one that flows through Bend? That flows north and into the Columbia River. And the Columbia River flows westward, collects all the water from the Willamette River near Portland, and continues past Astoria to the ocean. That is to say, anything that ends up in our river could easily end up in the ocean. Up to 700,000 fibers per load of laundry go into the greywater that goes into the wastewater treatment plant. Whew.

OPB recently put out a story about microplastics in Oregon’s rivers. Here are their results:

From “Hunt For Answers Shows Oregon Rivers Not Immune To Microplastic Pollution” by Jes Burns and Cassandra Profita, OPB. Notice what happens after the Deschutes passes through Bend. (Click on image for link to article)

I asked Julie whether she thinks our actions here in Bend — hundreds of miles from a coastline — have any impact on her studies and what happens in the sea. “Most definitely!” she replied. “Reducing waste will lessen the chance of material being transferred into the environment. Each time waste is moved, there is a percentage of material that falls onto the ground, washes into a stream, is caught by a wind current. Also, if every citizen uses less, the demand decreases and reduces the impacts in all municipalities including coastal states.”

Ok, now what?

Everything on earth is connected in one way or another. So here are a couple of waste reduction tips for you in regards to microplastics and our environment:

- Put a filter on your washing machine: The Cora Ball collects microfibers while in the washing machine, or the Lint LUV-R strains water that comes out of the washing machine.

- Bring your own cup, water bottle, utensils, and to-go containers!

- If you buy and use synthetic clothing, only wash it when you actually need to wash it.

- When buying home cleaning, self-cleaning, dog cleaning, any cleaning product, look at the ingredients and know what you’re buying. Does it contain plastics? If so, maybe you can find an alternative.

- Avoid buying things with unnecessary plastic packaging.

- Refuse freebies, handouts, and single-use stuff. I’m talking about cheap sunglasses, straws, and plastic swag.

- Do you need to buy it, whatever it is, in the first place?

In closing, Julie reminded me that even “the actions in the desert can transfer to all communities.” She says reminds us that it is important not to use too much and that we should all practice good waste hygiene. Thanks, Julie. That’s good advice.

What do you think?

You can’t see all the things down in the water when you’re standing on the deck. Learn more about Adventuress and her programs at www.soundexp.org.

Great article, Ani!

I learned a lot about our local contribution to plastic waste, and how it shows up in our rivers and oceans.

Nice work!!

Great article Ani and great work!

Thanks Cylvia!

Ms. Kasch, your piece is very enlightening and presented in a very concise, articulate, and easy to understand manner. A+

Thanks Mr. Robison!

Great article! I will share it with my middle school kids this fall!